Over-Articulation

Last article was about Mumbling, so, to be fair, this article will be about its opposite, Over-Articulation.

Over-articulation is, as one might guess, the process whereby we give too much energy to the articulation of our thoughts, dialling up the emphasis strategies we use to make words stand out beyond the needs of the situation or environment we’re in. Frequently, we hear over-articulation in the rate of speech (slower), in the stressing of operative words (lots of them, and very strongly and evenly), in the movement of the articulators (effortful, with lots of engagement of the facial muscles, as we signal our intent), and with more fortis release on voiceless stop-plosive consonants, [p, t, k] .

As we explored with the Mumble Method, there is something to be gained by exploring your natural impulse in over-articulating. By engaging in this, we can feel its possible negative side effects, such as habitual tensions associated with over-working, and if we notice how we’re doing it, we might possibly observe the emphatic strategies we’re over-using, and learn to turn them “for good, rather than evil.” So here’s my assignment to you right now:

Speak a text you have memorized, and attend to how you do what you do. I believe it helps to have a point of focus for this, so you’re speaking to someone (even an imagined someone) that you need to be crystal clear about something. I might help to dial up you need about this, as if you were speaking to an authority figure who just doesn’t get it, or someone who is frustrating you intensely in an extremely irritating manner. Go and play, and then come back and I will talk further about what I observe, and you can compare your results with mine. If yours are significantly different, or if you can think of further strategies than what I’ve outlined, I hope you’ll share your thoughts in the comments! (Don’t have anything memorized? That’s ok! Try a bit of invective from King Lear 2.2, or try a rant, or bit of bdelygmia [dəˈlɪɡmiə]…)

OK, you back? So let’s compare notes. Here’s what I noticed:

- increased pressure behind stop-plosives [p, t, k, b, d, g], and greater aspiration behind [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ]

- releasing final consonants, especially stop-plosives,

- lengthening final fricatives,

- being sure to fully voice final voiced consonant sounds

- exaggerating the sibilance of /s/ sounds (their hissy-ness)

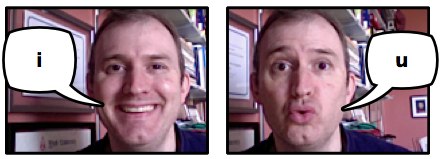

- greater lip-rounding on rounded vowels, such as [u, ʊ, oʊ, ɔ, ɒ], and on rounded consonants [ʃ, ʒ, tʃ, dʒ, w, ʍ]

- greater lip-spreading on spread vowels, especially [i] and possibly [ɪɚ].

- louder speech throughout,

- emphatic strong emphasis on many operative words that are regularly stressed “on a beat”

- tendency to glottalize initial vowels

- choosing to use dictionary-form or strong-forms of word pronunciations (e.g. a word like “our” gets bumped up to [ʔaʊɚ], and an elision like “gonna” gets elevated to “going to” [ˈgoʊ.wɪŋ ˈtu].

- consonant clusters may introduce small schwa-like releases of stops to make them more emphatic (e.g. “gleams” becomes [gəˈɫimz])

- with the greater effort may come habitual tensions in the neck, throat, tongue root, face, shoulders, chest, breathing mechanism, etc.

- either more even, or more dynamic intonation patterns, and other prosodic elements

As with the discoveries we discussed with the Mumble Method, this can lead us to realizations about over-articulation. This means we need to dig in and see which of these features we could use maybe one at a time, or maybe several at once. This will take some practice and exploration, but we can find a way to make this bad habit into a good practice. If the theory is that over-articulation is merely over-emphasis, all we may need to do is choose fewer words to emphasize and we’ll get a more balanced approach. Naturally, we want to leave out any of the patterns that involve excessive tension, effort, over-enunciation—moving the articulators too grossly.

How can we do this effectively? I would suggest that you start with a piece of text that is written out. Then go through with a pencil and underline two or three emphatic words per sentence. This will give you a smaller number of words to emphasize. Then, using the strategies we’ve outlined above, go through and try doing things like:

- energizing your stop-plosive consonants

- aspirating [pʰ, tʰ, kʰ], especially at the ends of phrases, before a pause or punctuation mark

- finding ways to put your emphasized words on a regular beat

- lengthen or relish final fricatives, and make sure that voiced final consonants are fully voiced.

Over articulation can be a bad habit. But it can also be a pathway to discovering more about what makes your speech interesting, audible, and most importantly, intelligible.