The Emphasis Recipe

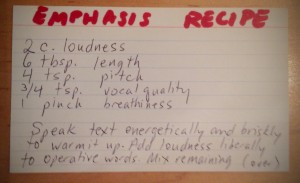

As the other posts in the Intelligibility Series have very clearly outlined, I strongly believe that intelligibility is a question of balance. Finding the right way to balance the language you speak will go a long way toward making your speech more intelligible. Our language often lacks this quality when we’re overly emphatic, and so finding a way to make our ideas pop out without overdoing it is essential. How do we emphasize a word or a phrase?

As the other posts in the Intelligibility Series have very clearly outlined, I strongly believe that intelligibility is a question of balance. Finding the right way to balance the language you speak will go a long way toward making your speech more intelligible. Our language often lacks this quality when we’re overly emphatic, and so finding a way to make our ideas pop out without overdoing it is essential. How do we emphasize a word or a phrase?

Let’s start with a bit of text from a play, and play with how we might choose to emphasize words within it.

BIFF. (With frustration.) Well, I spent six or seven years after high school trying to work myself up. Shipping clerk, salesman, business of one kind or another… and it’s a measly manner of existence. To get on that subway on the hot mornings in summer; to devote your whole life to keeping stock, or making phone calls, or selling or buying…. To suffer fifty weeks of the year for the sake of a two-week vacation when all you really desire is to be outdoors, with your shirt off. And always to have to get ahead of the next fella… And still… that’s how you build a future. —Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller (1949).

Read the text. Start by doing it the wrong way, by trying to emphasize as many words as possible. (Oh, it’s just wonderfully awful to do!) Now, try looking for far fewer words to emphasize, one or two per sentence. Read the text again, but this time, notice how you emphasize those most important words.

Let’s focus in on just one sentence: “…and it’s a measly manner of existence.” Let’s assume that you like that word measly as a word to emphasize. (I could be easily convinced that, with the alliteration on manner, you might want to emphasize it, too!) So emphasize that word:

…and it’s a measly manner of existence.

How did you do that? Maybe you gave it a bit of “punch.” Try that: punch while you say the word.

…and it’s a measly <punch> manner of existence.

With the punch, vocally you probably made the sound of the word louder. The /m/ sound at the beginning might have popped a bit more aggressively, but other than that, it was probably pronounced much the same way as you would if you hadn’t emphasized it.

Loudness isn’t the only way to emphasize a word. Another strategy you might have tried is to lengthen the word.

…and it’s a m e a s l y manner of existence.

By lengthening the word, the quality of its meaning seems (to me) to be emphasized. Remember that the OED tells us that, in this context, measly means “Inferior, contemptible, of little value; paltry.”

So far in our recipe for emphasis we’ve tackled the ingredients of length and loudness. The third ingredient is pitch associated with intonation. To continue our “words that start with L” alliteration, maybe we could go so far as to say “lift or lower” important words… (ok, maybe that’s too far!) In other words, use pitch to make words pop out, rather than generally making your voice higher or lower. So you might try the phrase we’ve been working on, first by pressing down pitch-wise on the word, and then by flipping up onto it.

…and it’s a measly manner of existence. OR …and it’s a measly manner of existence.

I prefer the former, personally. There are, of course, other ways to emphasize important words in a text, but loudness, length and pitch are the most common ones. For instance, one could change the vocal quality of a word to make it stand out. On our text you might, far a lark, try out something like some vocal fry (aka creaky voice) or nasality or breathiness on the word measly.

…and it’s a measly <vocal fry> manner of existence.

I find that a little odd, to be honest with you, but you get the idea. So now, let’s go back to the text, and experiment with these four things. I set out the text again, and I’ll emphasize words that seem important to me, though you could choose any word that spoke to you, too:

BIFF. (With frustration.) Well, I spent six or seven years after high school trying to work myself up. Shipping clerk, salesman, business of one kind or another… and it’s a measly manner of existence. To get on that subway on the hot mornings in summer; to devote your whole life to keeping stock, or making phone calls, or selling or buying…. To suffer fifty weeks of the year for the sake of a two-week vacation when all you really desire is to be outdoors, with your shirt off. And always to have to get ahead of the next fella… And still… that’s how you build a future. —Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller (1949).

You’ll note that I emphasized only the stressed syllables of the words I chose. (I don’t think that these words are better than any others; in fact, I suspect that many of these word choices are poor ones! Making mistakes in this kind of thing actually helps you learn what the line really means, so making mistakes is a good thing.) Not all the emphasized words are very important. Some more than others, some less so. I have probably still emphasized too many words; less is more. Try one more time, in order to explore the idea of how few words really need to get emphasis.

In order to explore pitch, you might make the surrounding text more monotone, so you feel the contrast more. To explore length, try making the rate of your speech fairly even, and then lengthen a word here or there, or speed up through a short phrase. Rush through a less important bit to linger longer on something substantial. For example:

<rush>to get on the subway on the <lengthen>hot mornings in summer.

As always, the key to intelligibility is balance. Take your time, explore language, and seek the path where what you’re trying to communicate is shared effectively and efficiently, not in a belaboured manner. With the right measurements of each ingredient, you’ll have a balanced recipe for your work.