Sniffing up the Ribs

In reviewing the site, it appears to me that the big hole in what’s on offer at this point is exercises about the ribs. The philosophical choice to come to ribs later in the process is based on the idea that you need a strong foundation in abdominal breathing first, and then awaken the ribs next. If this site was the only introduction you had to voice, breath and speech work, up to this point you’d be missing out on something I think is quite important.

We all breathe with our ribs. The movement of the ribs is generally something we don’t need to think about on a minute-by-minute basis, and for some of us, when we do think about engaging our ribs in our breathing process, the action tends to move up, toward the shoulders and the collarbones. Generally speaking, when we talk about breathing in the ribs, we want to avoid extra movement in an upward direction, and rather focus on breath in an outward dimension.

Our ribs are attached to the spine in the back, and, by way of cartilage, are connected to the sternum or “breast-bone” in front. We move our ribs via muscles that are in between our ribs, called intercostal muscles. There are two sets of these muscles: internal ones, that are on the sides and front of the ribcage, and external ones that are on the sides and back. The internal muscles are muscles of exhalation (breathing out), wile the externals are muscles of inhalation (breathing in.)

To engage your external intercostals, place the backs of your hands on your side ribs and, with your mouth closed, sniff 4 or 5 times, as if you were inflating your side ribs. When you feel full of air, just relax and let gravity and the elastic recoil of your lungs and ribcage send the air out. Then try the sniffing again.

Now that you’ve done that twice, take some time to feel the bottom edge of your rib cage. Press firmly around your bottom ribs, and feel how the bones can move due to the flexibility of the cartilages. Now grip the bottom of your side ribs with your thumbs pointing back and your index fingers pointing forward. Take one long, slow sniff into your sides, and push back with your hands a little; that way you can really feel the movement of the ribs. Again, when you’re full, just let the air “fall out”. All through this you want to try to keep your sternum relaxed so you’re opening your ribs wide, not puffing out your sternum forward.

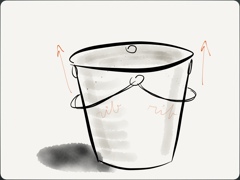

The best metaphor I think for what is happening here is to imagine a bucket with two handles, each handle hanging down on the side of the bucket. The hinges where the handles are attached represent your sternum in front and your spine in the back. As you inhale, the external muscles pull the ribs upwards, which expands the space inside your lungs gets bigger, and air rushes in to fill that space. You can see an illustration of this action here.

The best metaphor I think for what is happening here is to imagine a bucket with two handles, each handle hanging down on the side of the bucket. The hinges where the handles are attached represent your sternum in front and your spine in the back. As you inhale, the external muscles pull the ribs upwards, which expands the space inside your lungs gets bigger, and air rushes in to fill that space. You can see an illustration of this action here.

Next blog post, we’ll talk about the action of the internal intercostals in exhalation.

Nice post, Eric. I appreciate these, as they help clarify some things. A question: Is the sniffing an actual exercise or a way to help the reader understand your points?

-Joe

The sniffing is both an exercise and a way to explore the anatomy. I guess the post focuses on the anatomy an awful lot, rather than on “just do this!” I am hoping that this will be the first in a small series on rib breathing, so this is just a starter, laying the ground work for further explorations, each of which should have an exploration component and a “do it” (exercise) component.

I have used the sniffing as a way to bring awareness to the nasal passage for nasal resonator work. I can see how it can be used for breath work, as well…

It is worth pointing out that I don’t normally use nose-breathing as a teaching mode. It’s useful because it really opens up the arytenoid cartilages and you can get a very quick connection to the side ribs. It’s a great wake up call to that area!